Lisbon is currently hosting EuroPride 2025, taking place from June 14 to 22. This marks the first time the event is being held in a Portuguese-speaking country.

EuroPride is the largest annual pan-European event dedicated to LGBTQIA+ rights and culture. It features not only a vibrant pride parade (scheduled for June 21), but also a wide range of cultural, political, and educational events focused on promoting equality, increasing visibility, combating discrimination, and strengthening solidarity across Europe. Lisbon has been celebrating its own local pride event, Arraial Lisboa Pride, since 1997, usually held in June.

As part of this topic, if you're currently living in Portugal, we invite you to take part in our ongoing survey. While we've already begun collecting responses for this article, we’re continuing to gather voices to better understand public attitudes toward LGBTQIA+ rights in the country.

Interestingly, results from our survey show that 86.5% of participants consider pride parades important for society. Many respondents elaborated, emphasizing that Pride is not simply a colorful show, as some might assume, but above all a powerful form of activism and a fight for visibility. Events like these send a clear message: queer people are part of society, with the same rights, emotions, and humanity as everyone else. Of course, a little celebration, color, and masquerade are also essential to the spirit of Pride.

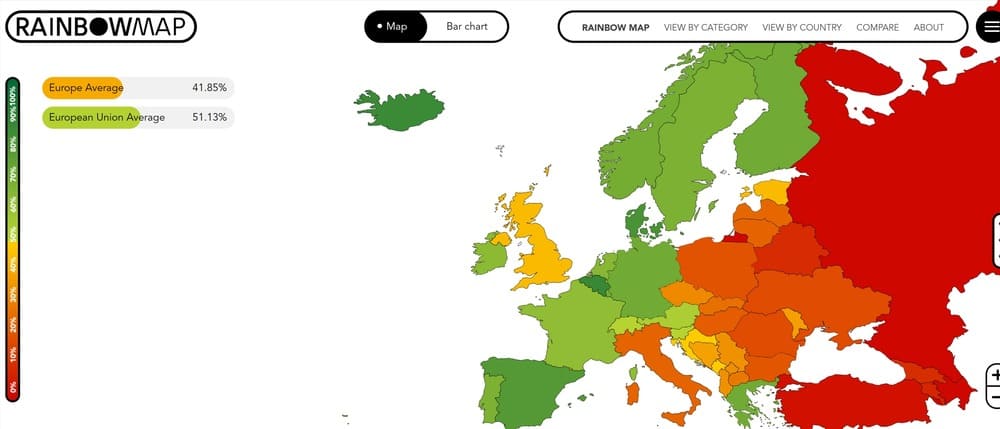

But let’s get back to the topic. EuroPride has given us a reason to take a closer look at the current state of LGBTQIA+ rights and freedoms in Portugal, a country often ranked among the most tolerant in Europe. This reputation is reflected, for instance, in the Rainbow Map, which rates 49 European countries based on their legal and political practices concerning LGBTQIA+ people, using a scale from 0 to 100%, where 100% represents the highest level of protection and equality for queer communities. Portugal ranks 11th on the list with a score of 66.99%, behind countries like Denmark (80.10%) and above the EU average of 51.13%.

In our recent survey, where only about half of participants identified as queer, 70% said they had never personally experienced discrimination based on gender identity or sexual orientation. Meanwhile, 60% believe that such discrimination in Portugal either does not exist or is minimal, and another 20% consider it to be moderate.

In this article, we’ll explore several key aspects:

- Legislation: the current laws affecting the rights and opportunities of queer people;

- Politics: the stance of Portugal’s ruling parties on LGBTQIA+ issues;

- Immigration and human rights: what protections are available for those fleeing persecution based on sexual orientation or gender identity, and how Portugal handles such cases;

- Community engagement and support: what organizations are active in the country, and where to turn for help or information;

- Public attitudes: how Portuguese society at large views LGBTQIA+ people, and how safe queer individuals feel in daily life.

Together, these topics help paint a fuller picture behind the flags and slogans, and show whether Portugal truly remains one of the safest countries in Europe for LGBTQIA+ people. And if you're curious about the history of the queer movement in Portugal, you can take a look at this article or this one, where the most important milestones are mapped out.

Legislation for queer people.

In many aspects of supporting the queer community, Portugal is undoubtedly one of the most progressive countries in Europe. All individuals are guaranteed equal rights. For example, trans people are allowed to serve in the military, and gay men can donate blood without any restrictions.

Already in 2001, Portugal granted equal legal rights to same-sex couples through civil unions, and in 2010, full marriage equality was introduced (Lei n.º 9/2010, de 31 de maio). Same-sex couples enjoy the same rights as opposite-sex couples, including the ability to share parental leave and have both names listed on a child’s birth certificate. They are entitled to joint health insurance, shared bank accounts, inheritance without additional taxes, family reunification rights for legal residency, joint property ownership, tax benefits for families, access to medical information about their partner, and the right to make emergency decisions on their behalf. By the way, getting married in Portugal can even be done online.

In 2016, the law was amended again, eliminating discrimination against same-sex couples in matters of child adoption (Lei n.º 2/2016, de 29 de fevereiro).

Then, in 2018, Portugal passed a law granting the right to legal gender recognition without requiring a medical diagnosis or surgery (Lei n.º 38/2018, de 7 de agosto). This means any citizen aged 16 and over can change their legal gender and name through a personal declaration, no medical or psychiatric reports needed. The law also includes protections for intersex individuals (those born with natural variations in sex characteristics), prohibiting non-essential medical procedures on infants unless medically justified.

Let’s highlight not just the laws that grant rights, but also those that offer protection:

- A constitutional guarantee of equality and a ban on discrimination, including on the basis of sexual orientation (Constituição da República Portuguesa – Article 13).

- A ban on workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity, or other factors (Labour Code – Articles 24 and following).

- Criminal code provisions that address hate crimes, incitement to discrimination, and harsher penalties for hate-motivated offenses based on sexual orientation or gender identity (Penal Code – Articles 132, 240, and 246).

In our view, progressive legislation is already more than half the journey toward a more tolerant society. If you belong to the queer community and are considering immigration, choosing a country that not only avoids restricting your civil and human rights but actively protects you from unlawful discrimination is crucial.

Across the EU, the situation remains uneven: some countries still haven’t legalized same-sex marriage or even civil unions; in others, gay men still face blood donation bans, and trans individuals are not allowed to serve in the military.

In our survey, we asked whether Europe should adopt a unified standard of rights and freedoms for LGBTQIA+ people. Between 75% and 79% of respondents answered “yes,” depending on the specific topic. The remaining participants felt that each country should retain the right to make its own policy decisions, a stance that doesn't necessarily reflect opposition to the issues themselves.

And what do you think?

The role of politics.

Let’s take a quick look at the political landscape as of June 2025:

- The Democratic Alliance (AD): center-right, currently holds 91 seats in parliament;

- Chega: far-right populists, 60 seats;

- Socialist Party (PS): 58 seats;

- Other groups, including LIVRE, the Left Bloc (BE), PAN, and others, hold fewer seats and play a less significant role in shaping LGBTQIA+ policy at the national level.

We’ll briefly outline where these parties generally stand when it comes to LGBTQIA+ rights.

The Democratic Alliance (AD):

This alliance brings together PPD/PSD (Partido Social Democrata), CDS–PP, and PPM. Out of the 91 seats won by AD, 89 belong to PSD, so our focus will primarily be on them.

PSD officially supports legal equality for LGBTQIA+ people and opposes discrimination, often emphasizing its historical role in decriminalizing homosexuality back in 1982.

However, the party is frequently criticized for harboring more conservative voices within its ranks and for refusing to back certain initiatives proposed by left-wing parties on queer-related issues.

One notable example was the proposed ban on “conversion therapy”: while PSD initially supported the concept, it ultimately voted against the final version of the bill, citing legal flaws in the draft.

The main divide between PSD and the left isn’t so much about the goals themselves, but rather the approach and the rhetoric used to get there.

Chega:

André Ventura, leader of the Chega party, is criticized for his authoritarian rhetoric and statements which human rights organizations, including ILGA Portugal, and some members of the public consider xenophobic and homophobic. Nevertheless, let’s take a closer look at his stance on our topic.

He states that “homosexuality does not diminish anyone” and presents himself as a supporter of same-sex marriage, adding that his party includes people of different sexual orientations, “even sometimes” in leadership positions. “I have many gay friends, some of whom are the brightest people I have ever met in my life, who speak very well of me and understand that I have never been hostile towards gay people or the LGBT community.”

On gender identity issues, he holds the view that this is not about human rights but about rights to transformation, which in turn are not universal.

The party leader also speaks out against pride parades, arguing that the marches and these movements “want to impose models and ideas on children and youth that do not represent Portuguese society.”

At the same time, part of the party, despite their leader’s stance, takes a more radical position regarding the rights and freedoms of the queer community.

According to our survey, where queer people make up 45 percent of respondents, as many as 74 percent of all are concerned about the growing popularity of Chega in the context of LGBTQIA+ rights, while 21 percent believe there will be no significant changes in rights and freedoms.

Socialist Party (PS):

They support specific legislation to protect LGBTQIA+ rights. They actively advocate for banning conversion practices and reforms in gender expression.

In January 2024, the Portuguese Parliament passed Law no. 15/2024, which prohibits and punishes (with up to three years in prison plus fines) any practices aimed at forcibly changing sexual orientation, gender identity, or expression — so-called “conversion therapies.” The law was initiated by groups of deputies including PS, BE, Livre, and PAN.

This party also supported the law we mentioned earlier granting the right to legal gender recognition without requiring medical diagnosis or surgery (Law no. 38/2018, August 7).

At present, we conclude that the main rights and freedoms are unlikely to be threatened by the current parliament, although there may be debates on issues like including certain materials in school education, coverage of gender reassignment surgeries by insurance, and similar topics.

It is notable that there are openly queer politicians. For example, Graça Fonseca from PS served as Minister of Culture from 2018 to 2022 in António Costa’s government and is one of the first publicly openly gay figures in the Portuguese government. Fabíola Cardoso from BE (Left Bloc) has been a member of parliament since 2019, is an openly lesbian activist, and actively advocates for queer rights, anti-racism, and education. Miguel Vale de Almeida from PS served as a Member of the European Parliament from 2009 to 2011 and was the first openly gay person in the Portuguese parliament.

Immigration and human rights issues.

LGBTQIA+ people have access to all available types of legalization in Portugal, including family reunification (D6), work (D1), or study visas (D4, D5), TechVisa for highly qualified IT specialists, startup visas, entrepreneur visas (D2), highly qualified professional visas (D3), freelancer visas (D8), passive income visas (D7), the Golden Visa, and asylum (alongside grounds such as race, religion, nationality, and political opinion). You can consult us to understand which visa option is best for you and your family.

We would also like to highlight asylum in Portugal. If a person faces threats, violence, forced “treatment,” or criminal prosecution, they can apply for asylum based on belonging to a vulnerable social group. Detailed information in multiple languages is available on the AIMA website.

LGBTQIA+ refugees, especially from countries where homosexuality or transgender identity are criminalized (such as Iran, Nigeria, Russia, Uganda, and others), may obtain international protection (refugee status) or subsidiary protection.

Refugee status is granted to those who have been or reasonably fear persecution due to their beliefs, origin, religion, political views, or membership in a particular social group, including LGBTQIA+. This recognition under the Geneva Convention provides full protection, long-term rights, and a path to citizenship. It is issued for five years, with the possibility to apply later for permanent residency or citizenship.

Subsidiary protection applies when a person does not meet the refugee definition but returning to their home country threatens their life or dignity, for example due to war, torture, death penalty, or widespread violence. This is a “second-tier” temporary protection granting basic rights. It is issued for three years with the possibility of extension. Obtaining permanent residency, citizenship, and family reunification later is possible but under more complex conditions.

Both statuses grant the right to live and work in Portugal, but refugee status is more stable and long-term. Both can be revoked if the reasons for persecution or risk disappear.

These two statuses should not be confused with the temporary protection granted to Ukrainians, known as Proteção Temporária. This is not refugee status and not subsidiary protection, but a special legal regime established by the EU after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It is typically renewed on a yearly basis and grants the right to work, as well as access to healthcare, education, and social services. However, unlike refugee status, it does not lead directly to permanent residency after five years.

In our survey, where half the respondents are Portuguese, 85 percent fully agree that protection for LGBTQIA+ should exist, while 9.5 percent agree but only for extreme cases.

Community support and activism.

Portugal is home to NGOs and grassroots initiatives that support LGBTQIA+ migrants and residents. If you need help, protection, or simply want to connect with like-minded people, you can reach out to one of the following organizations:

- ILGA Portugal. Based in Lisbon, founded in 1997, this is the largest organization in the country dedicated to defending queer rights. ILGA offers cultural and political activities, as well as a range of free services such as legal support and psychological counseling.

- Clube Safo. Founded in 1996 in Aveiro, this organization focuses on supporting and defending the rights of lesbians. It also organizes cultural events, develops political initiatives, and provides a space for dialogue, opinion exchange, and advocacy.

- Opus Diversidades. Established in 1997, this group focuses on LGBTQIA+ support, while also working with migrants and women. Their mission includes combating anti-immigrant and sexist policies. They offer shelter, psychological assistance, and general support. They also run a dedicated program for elderly members of the queer community.

- Casa T Lisboa. A housing project for trans immigrants created in Lisbon during the height of the pandemic. It receives no state funding and relies entirely on crowdfunding through the platform GoFundMe.

- TransMissão. A community of trans and non-binary individuals advocating for their rights. They are part of the organizing committee for the annual Pride parade and lead a number of initiatives in Almada, including Wardrobe Discovery, a safe space where people can explore different clothing styles and express themselves.

There are many other organizations, and we encourage you to search or network to find the ones best suited to your needs.

Several human rights and charity organizations also run programs supporting the LGBTQIA+ community. For example:

- Associação Plano i, based in Porto.

- CIG (Comissão para a Cidadania e Igualdade de Género), based in Lisbon.

Public attitudes.

To conclude this article, we want to briefly address how everyday Portuguese people and other residents view queer individuals and the broader conversation around their rights. Are people keeping pace with progressive legislation?

Portugal shows relatively high levels of public acceptance and tolerance. According to Eurobarometer 2019, 78 percent of Portuguese citizens support equal rights for LGBTQIA+ people — a number that continues to grow steadily.

Portugal has cities to live in and areas for leisure that are especially popular within the community. Lisbon, particularly the neighborhoods of Principe Real and Bairro Alto, is a well-known queer-friendly hub. In Porto, the eastern part of Rua das Oliveiras and the southern stretch of Rua da Conceição stand out. The Algarve region is also a favorite, including cities like Faro and Tavira, with Barril Naturist Beach being a notable spot. Almada and Caparica are also welcoming. In these areas, the level of social tolerance is often even higher.

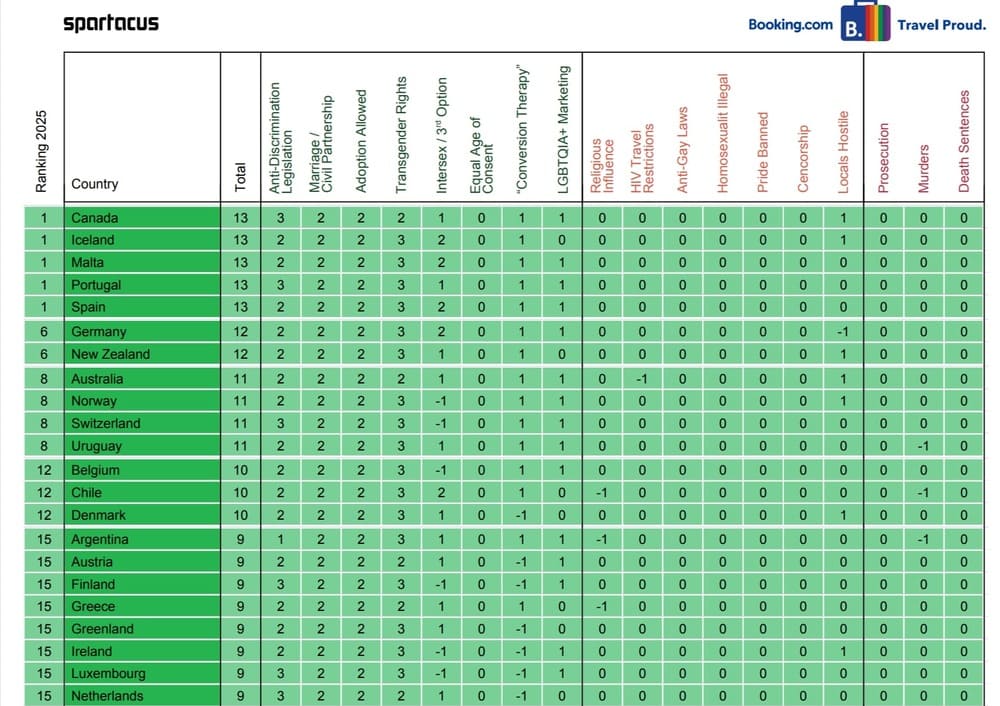

We can also look at a more recent study — the Gay Travel Index 2025, published annually since 2012. This index evaluates the legal situation and living conditions for members of the queer community around the world.

Portugal consistently ranks among the top countries on this list. Ukraine currently holds the 66th position.

In smaller towns, among older generations, or within immigrant communities from third countries, conservative views and latent homophobia may still persist. According to our own survey, such attitudes most often manifest through words, in public spaces or on social media, rather than through direct action.

Looking at actual hate crimes, authorities registered 347 incidents related to discrimination and hate speech in 2023, which is 77 more than in 2022. However, this figure includes all forms of hate, from religious bias to racial prejudice.

There have been anti-LGBTQIA+ protests in Portugal. For example, in 2024, a demonstration “against gender ideology in schools” took place in Lisbon, drawing about 100 participants. In another case, the far-right group Reconquista attempted to disrupt a local mini pride event in Évora, shouting slogans and clashing with police and attendees.

These protests remain small in scale, usually involving just dozens or perhaps a hundred people, and appear marginal when compared to the tens of thousands who attend Pride events. Still, they point to the presence of organized conservative groups capable of holding public demonstrations. It’s worth noting that such actions are typically suppressed or dismissed by police and civil society, and they receive no political backing from major parties in parliament.

We’ve aimed to give you a broad and honest picture of the current situation for LGBTQIA+ individuals. In our view, Portugal remains one of the best countries in the world for queer people.