The recent visit of the Pope to Portugal has significantly shaken up the lives of residents. Despite temperatures of more than 40 degrees Celsius, 1.5 million people gathered in Lisbon to see Pope Francis, who visited the city to celebrate World Youth Day.

This significant event for the inhabitants of the country demonstrated the importance of the Catholic religion among the population of Portugal. In this article, we will take a closer look at the place of this and other religions among the country's population, and what historical events led to the formation of the religious climate that exists here today.

It should be noted at the outset that Portugal is a secular state. The Constitution of the Republic of Portugal states that "freedom of conscience, religion and forms of worship shall be inviolable" (Article 41, paragraph 1) and that "churches and other religious communities are separate from the State and are free in their organization and in the exercise of their functions and forms of worship" (Article 41, paragraph 4).

At the same time, the predominant religion among the Portuguese is still Catholicism, which has played a major role in the development and formation of society throughout its long history. If you visit any of the local small settlements or towns, you will immediately see how much of a place in the life of the population has traditionally been given to the church: the main village churches are usually located in the center, or at least in a prominent place – in the central square or on top of a hill. Many of them were built in the 16th century, at the peak of Portugal's colonial expansion, and are often decorated with wood and gold leaf obtained during the conquests. However, in recent decades, many have fallen into disrepair due to a lack of priests to provide them with proper care, and are now used only occasionally, mostly to honor patron saints.

However, this was not always the case. Throughout the long and rich history of the country's development, various religious processes have taken place here, which we will now briefly consider in the historical context.

As we have already noted, religion, in particular Catholicism, has played a significant role in the social and political life of Portugal throughout its history. The Christianization of the lands of the modern territory of the country began in the 4th and 5th centuries, and already during the Byzantine Empire, Orthodoxy and other religious traditions began to spread on the Iberian Peninsula. In the Middle Ages, Portugal became an independent kingdom, where the Catholic Church had a great influence on social and political life. Thus, in the 12th and 13th centuries, a brotherhood was created to protect Christianity from Muslim attacks. Subsequently, Portugal, as you know, entered the Age of Discovery, and secured the title of superpower of that time due to its remarkable success in this field. Navigators and explorers expanded the boundaries of the familiar world and came into contact with other cultures and religions, learning from their experiences, exchanging views and teachings. Later, the religious background of the country was greatly shaken by the Inquisition: the Catholic Church actively fought against heretics and tried to convert Jews and Muslims. This era, of course, was marked by a period of many conflicts and strife in the religious development of society.

20th century and modernity

The current situation in the country began to take shape in the 19th and 20th centuries, when secularization processes began to take place in Portugal, that is the influence of religion on the life of the population began to decline. The church lost some of its power, despite its brief rise in 1932-1968 under Salazar, when the family, parish and Christianity were considered the foundations of the state, until the establishment of a dictatorship where these principles were taken as the basis. However, restrictions and bans on the freedom of the population to practice their religion finally changed after the Carnation Revolution in 1974; the Constitution was rewritten, the Catholic Church and the state were formally separated, and since then, society has become markedly secular: the practice of religion has declined. By the early 1990s, most Portuguese still considered themselves Roman Catholics in a cultural and religious sense, but only about a third of them regularly attended Mass, mostly women. Religious rituals and traditions also continued to circulate in society with their support: for example, the image of the Virgin Mary, as well as the image of Christ, could be seen even in trade union offices or on signs during demonstrations.

It is worth noting that a significant part of the country's religious life traditionally took place outside the official structure and territory of the church, and closely coexisted alongside a wide variety of beliefs and superstitions, or phenomena such as magic and witchcraft. Almost every village had its own "seers", "wizards" and "healers". Especially in the most remote regions of northern Portugal, belief in witches and evil spirits was widespread. Some people also believed in such phenomena as the "evil eye" and were afraid of those who allegedly practiced it. It was believed that werewolves could be found in the mountains and on the roadsides, and one had to be especially careful not to run into one of the "evil spirits".

Some beliefs gradually declined with the development of education and the migration of people to cities, although even in the early 1990s, superstitions were spreading there, against which the church was powerless. In the villages, the traditions of honoring saints and celebrating religious holidays continued to be maintained.

Until now, the most famous of these celebrations is the apparition of the Virgin Mary, who appeared to three shepherdesses in 1917 in the village of Fatima. The apparition of the Heavenly Mother in this small village in the Santarem district prompted hundreds of thousands of pilgrims to visit the Fatima Shrine of Our Lady every year in the hope of receiving healing.

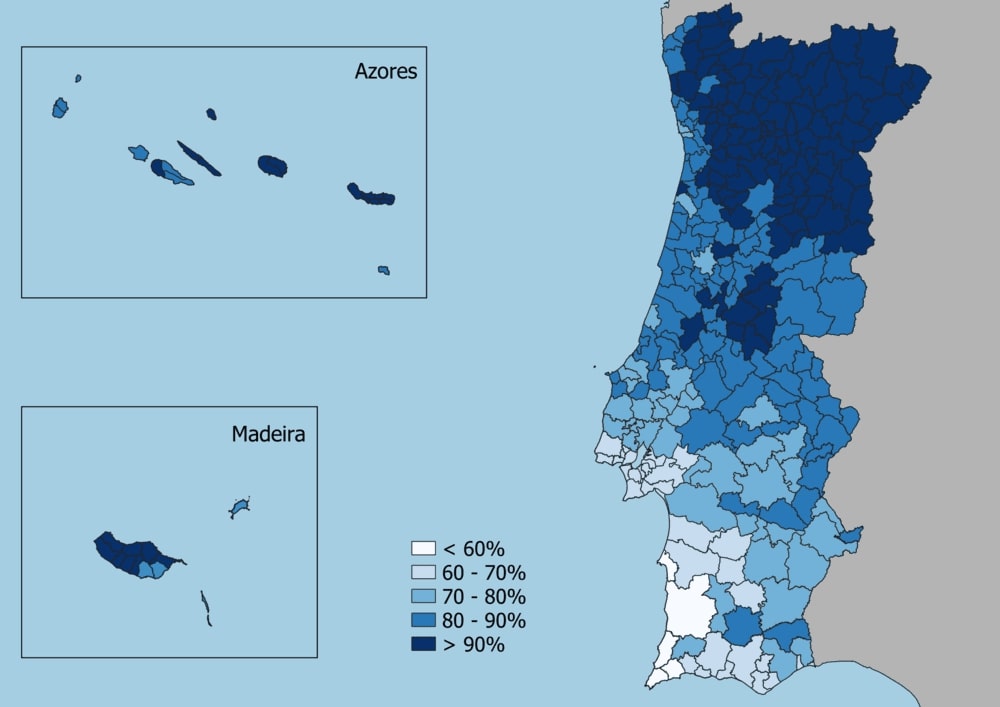

It is worth noting that strong differences in religion among the Portuguese can be seen not only in the rural/urban ratio, but also in different areas of the country. If we look at the change in trends over the years, already in the early 1990s, 60-70% of the population of the northern regions regularly attended religious services, while in the south this number was 10-15% (30% in Lisbon). At the same time, the Catholic Church remained an important sociocultural factor throughout the country, but now other religions, such as Islam, Protestantism, Judaism and others, coexist alongside it, and the religious landscape, as we can see, is surprisingly diverse.

Thus, the Roman Catholic Church still occupies a dominant place in the lives of local citizens, and about 81% of the Portuguese population consider themselves Roman Catholics, however, most do not practice Catholicism, that is do not actively attend services and do not celebrate religious holidays. For many, the traditions of Catholicism are a kind of heritage that has become one of the defining features of their national and cultural identity, not just a sign of religious affiliation.

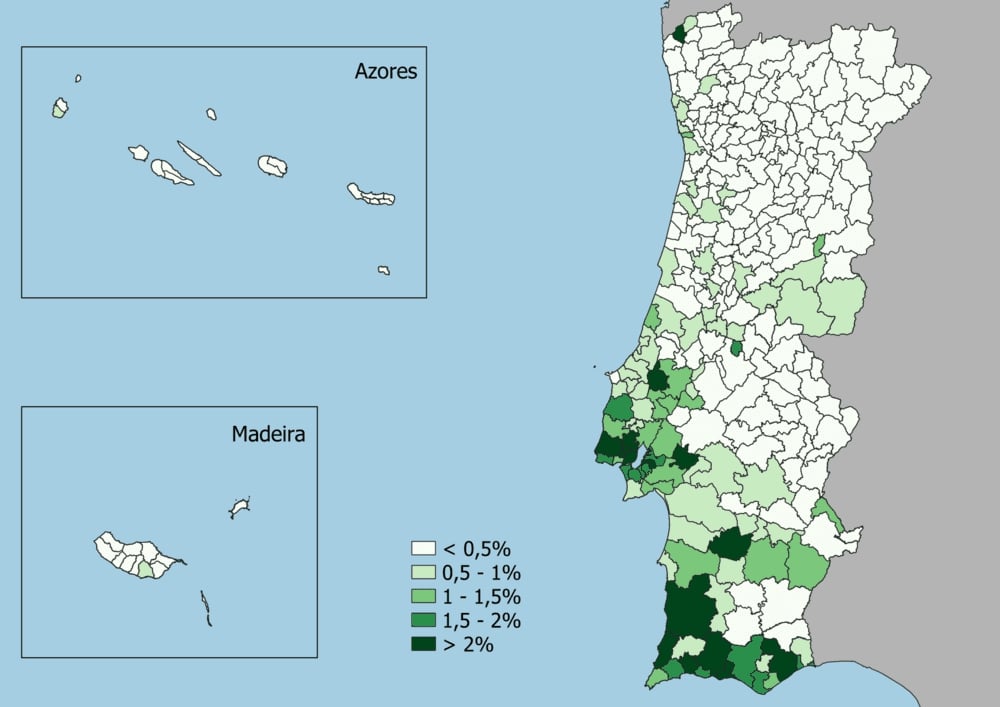

As for the rest of the population, in addition to Catholicism, there are also representatives of other religions and faiths in Portugal, such as Protestants, Muslims, Jews, Buddhists, and others. With the growth of immigration to the country over the past decade, religious communities from different parts of the world have formed here, which has led to an increase in the diversity of religious beliefs.

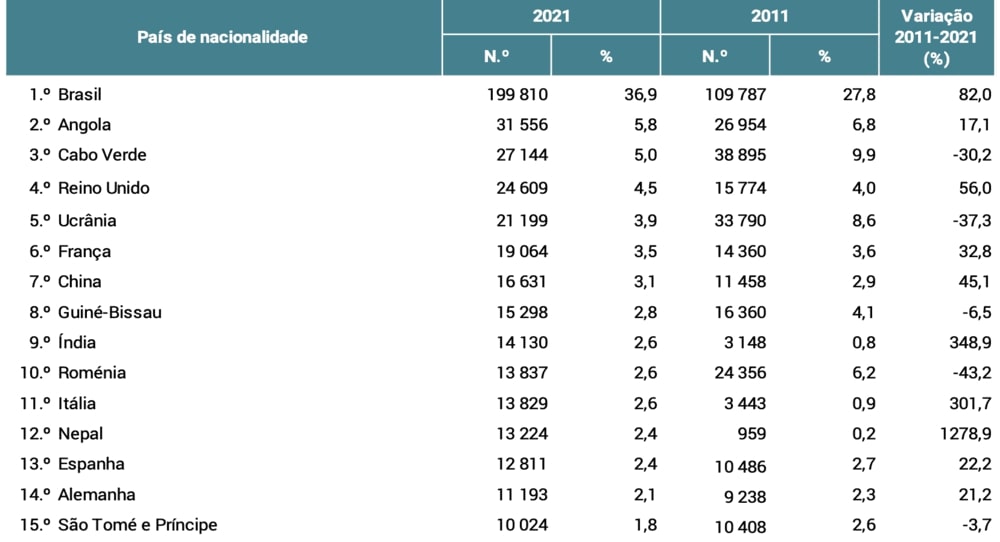

For a better understanding, we can look at the following table, which provides comparative data for 2011 and 2021. Of course, it is worth making an allowance for the fact that the number of migrants, which was already quite high before, increased after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine.

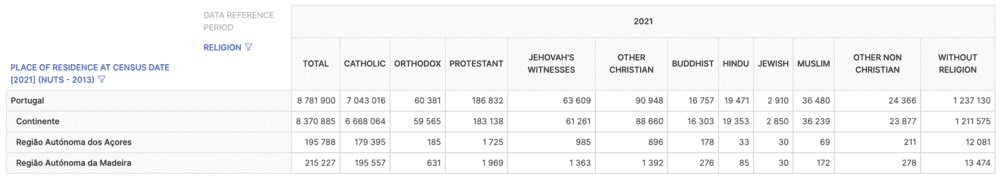

Currently, the vast majority of those who consider themselves believers, namely 3.3%, identify themselves with another denomination of Christianity, 0.6% – with another religion (including professing Judaism and Muslims), 6.8% do not consider themselves to belong to any religion, and 8.3% did not indicate a religious affiliation.

This table shows data from the mainland, the Azores, and Madeira, where you can see the proportion of people who professed (or not) a particular religion as of 2021:

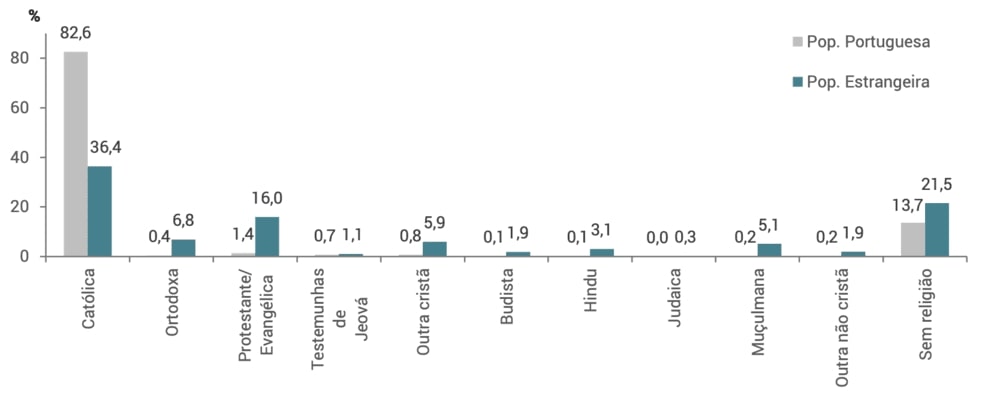

It should be added that, given the multinational nature of the country and the large number of migrants mentioned earlier, there is a certain difference in the affiliation to different religions among the residents of the country who are Portuguese by nationality and foreigners living in the country, who currently make up about 5.2% of the population.

Thus, while more than 80% of Portuguese respondents consider themselves Catholics, only 36.4% of foreign nationals belong to the Catholic Church. And while about 3% of Portuguese nationals identify themselves with another Christian religion, among foreigners this number reaches 30%. At the same time, a significant number of them are followers of Protestant/evangelical (16%) and Orthodox (6.8%) denominations. Furthermore, among foreigners, the number of those who consider themselves to be a representative of another religion is 12.3%. In general, the rates of those who profess non-Christian religions were higher among the foreign population, for example, 5.1% of Muslims and 3.1% of Hindus. 13.7% of Portuguese and 21.5% of foreigners do not belong to any church.

This can be seen in more detail in the table below, where gray indicates Portuguese by nationality, and green indicates foreigners.

As we can see, the diversity of different religions in the country has created a developed environment for their practice: there are rarely cases of discrimination on religious grounds, all faiths and denominations usually coexist peacefully with each other, and believers find plenty of opportunities to follow the lifestyle dictated by their religion. At the same time, the Catholic Church remains an important sociocultural factor until now.

Translated from Ukrainian by Rodion Shkurko