Everyone who is even a bit familiar with Portuguese life knows about the cold and dampness of Portuguese homes in winter. Behind this phenomenon, seemingly easily explainable by the laws of nature, lies a complex social problem called energy poverty. It is defined as the inability of a household to obtain the necessary level of any domestic energy services, the lack of which causes discomfort or hardship to household members. In a situation of energy poverty are, on the one hand, families who spend a tangible portion of their income on energy consumption. On the other hand, people who deliberately limit their energy consumption to uncomfortable levels to avoid excessively high costs.

In this article, we will try to understand what constitutes energy poverty in Portugal, how the state is fighting this issue and what is the criterion for choosing energy-efficient housing.

The causes of energy poverty in Portugal

In Europe, energy poverty is considered a serious difficulty, the consequences of which are seriously detrimental to health, well-being, and social engagement. With the pandemic, where people have had to spend much more time at home than before, the relevance of energy services in most aspects of daily life, including work, education, entertainment, and being comfortable at home, has only increased.

Why is there energy poverty in Portugal? There is no short answer to this question. Several factors contribute to the problem simultaneously:

- Poor quality housing

The processes of industrialization and urbanization in Portugal began rather late, and the government's housing policies were not always targeted. A serious housing shortage in the second half of the 20th century provoked a surge in illegal construction and self-building, as well as an increase in slums, especially in Lisbon and Porto. It is estimated that in the 1970s, about 40 percent of residential buildings in the country were unlicensed. To make housing more affordable, during the Estado Novo dictatorship a rent freeze was introduced, but its extension had detrimental consequences, including a lack of investment by landlords, which contributed to the deterioration of housing quality. In contrast, in other European countries since the early 20th century, housing affordability, value, and quality have been vigorously promoted under welfare state policies. In Portugal, it was not until the 1990s that any requirements for how warm a residential building should be to be legislated, and before that, the level of insulation of the housing stock was even lower.

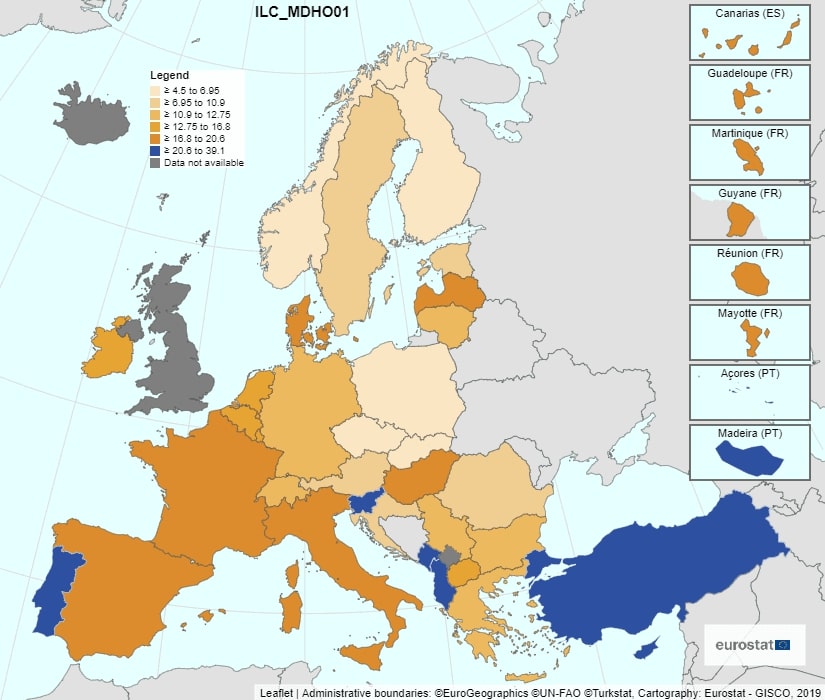

In addition to the poor quality of home construction, many households are financially unable to make repairs. Problems exist not only with the maintenance of heat. For example, according to Eurostat, in 2020, a quarter of Portugal's population (25.2%) lived in homes with leaks, damp or rotten windows or floors. In the map below, you can see that Portugal is one of the European leaders in this indicator.

- Commitment to tradition in construction

Traditionally, in Portugal, houses are built without heating systems or with only a fireplace (which is very inefficient because it loses more than 80% of the heat produced and requires considerable physical effort to maintain). This is a building practice that is rarely seen in other EU countries (except Malta and Spain), where almost all houses have central heating systems or other fixed systems. In the EU, natural gas is most often used to heat homes. In Portugal, the majority of the population does not have such a possibility. Only 34% of households in the country are covered by the gas distribution network since the second half of the 1990s, and they are mostly located in large urban areas. The majority of the Portuguese population, especially the economically disadvantaged, still use bottled gas, which is more expensive than pipeline gas and is not sold at preferential rates.

- Low-energy efficiency of household appliances

Without stationary heating systems, most of the population uses cheap electric portable heaters. As you can guess, the low cost of devices means also their low efficiency and, accordingly, high operating expenses. Some people are afraid of high electricity bills and therefore stop using heaters altogether. And some, especially lower-income Portuguese, use their appliances until they no longer work, even if they are already inefficient, as is often the case with refrigerators, freezers, or televisions. When buying any appliance, the poorest always choose the cheapest models, not considering future electricity costs.

- The habit of enduring the cold

A combination of several factors has led to the fact that in Portugal, the practice of heating the house in winter with modern equipment is not widespread. In Portugal, preference is given to the use of warm clothes and shoes or blankets rather than heating the room. Except for fireplaces, heating equipment is generally used only on the coldest days and in a very limited way: only in those rooms of the house where it is most needed and for the shortest possible periods. The use of electrical equipment for individual heating (such as electric blankets) is also very limited. Other common ways to stay warm include staying in bed longer or going to bed earlier, using warmers, eating hot food and drinks, or, weather permitting, going outside. The main reason that heating equipment is not used more often (or at all) is economic, so cold in the home becomes the norm.

- The habit of enduring the heat

Electric devices to fight the heat are used carefully. Although since the mid-2000s, air conditioners have been actively installed in Portuguese homes (it has become common to include them in new buildings beforehand), they are still not common among citizens, who are the most economically vulnerable. The methods developed by the population to combat the heat consist mainly of regulating the internal temperature of the home through natural ventilation (i.e., opening windows and doors). It is also important to protect against excessive solar radiation and the intrusion of hot air from outside. Other common methods include adapting clothing, lowering shower water temperature, moving from warmer rooms to cooler ones (such as sleeping on a lower floor), and drinking more water (or other drinks).

The use of fans is generally avoided because of the cost of energy and the fear that it will affect people with respiratory disease and an aversion to forced air circulation. When this occurs, the use of fans is limited to hot days only and usually only for short periods of time.

- Underestimating the severity of winter cold weather

The notion that winters in Portugal are short and mild and that it was colder in the past leads to a psychological devaluation of cold in the home, encouraging the use of inexpensive measures to combat cold, and thus deterring people from investing in efficient heating equipment and major home repairs. At the same time, there is a perception that periods of extreme heat are becoming more frequent and intense due to climate change. This encourages people to purchase equipment to help fight the heat. There is simply no money left over to fight the cold.

- The perception of heating as a luxury

In Portugal, home heating is neglected, considering it normal and acceptable to feel cold in winter. Not being cold at home in winter is considered a luxury, so instead of spending money on heating or on work to insulate the house, people prefer to spend it on other household needs that are considered more urgent. Thus, there is a high level of tolerance for cold that is not limited to low-income people. This tolerance or resignation to discomfort is reinforced by a social acceptance of energy conservation, which also extends to other energy services such as lighting, washing clothes, or cooking. In this sociocultural context, many citizens prefer not to use energy services rather than incur costs that they cannot afford or that they consider too high.

If we compare with other EU countries, according to Eurostat, in 2021 Portugal was in 2nd place from the end by the share of energy used by households to heat their homes (30.8%). For comparison, the highest share was then observed in Luxembourg (80.3%).

- High cost of energy

The cost of energy can greatly affect consumption. Recently, electricity prices for households in Portugal have been among the highest in the EU. According to Eurostat, Portugal was even the country with the most expensive electricity for households in the second half of 2018, and gas prices were also among the highest in the EU (of course, if energy prices are compared at purchasing power parity). That year, the taxes, and fees included in Portugal's electricity bills accounted for 55% of the final price. Thus, in a sociocultural context in which it is considered normal to freeze in winter, many Portuguese prefer to keep heating costs to a minimum.

- Low income

Depressing dynamics of reducing economic inequality in the country from the mid-1990s to the end of the 2010s. The economic crisis and the austerity policies that followed reversed this trend, leading to deterioration of living conditions and impoverishment of the population. The pandemic and its serious economic consequences worsened the living conditions of many Portuguese, especially those who were already more vulnerable. Low incomes can not only prevent families from using the energy services they need, but also affect their ability to buy or repair household equipment.

- Citizens' lack of confidence in energy service providers

Liberalization of the energy market and some changes in the sector have made energy supply more difficult because of the increase in the number of suppliers, contract terms and differences between distribution networks and energy suppliers. This has led to uncertainty and insecurity, especially among the most vulnerable citizens. Many are afraid to change suppliers and have had negative experiences with aggressive sales.

- Low level of public awareness

Due to various historical and structural factors, Portugal's literacy and education levels remain lower than in most other EU countries. Despite the evolution in a positive direction, this scenario continues to affect the literacy of adult citizens and their ability to deal with complex issues such as energy consumption. People often have difficulty understanding the energy contract (especially when it is not about simple tariffs, when there are "discounts" or when other services are added). Difficulties also arise in estimating the energy consumption of household equipment, except for the notion that electric heaters, refrigerators, and ovens are among the ones that consume the most energy. Observing how the electricity meter runs faster when some appliances are plugged in, and the fact that the electrical switchboard shuts down when some appliances are plugged in at the same time. These are important and intuitive ways that citizens use to estimate equipment power consumption. But the fact that electricity is supplied uninterrupted, associated with estimated or fixed monthly billing and the possibility of periods with different rates, makes it difficult to understand the relationship between energy use and cost. This is unlike what happens with other forms of energy sold per unit, such as gas in cylinders.

How many Portuguese are in energy poverty

According to the factors listed above, there are 4 main indicators of energy poverty.

- The population living with an inability to maintain an adequate level of heat in their home is 18.9% of the total population of Portugal (1.9 million people).

- Households that benefit from preferential electricity rates - 752,956 households (1.9 million people).

- Households that enjoy preferential gas rates - 34,709 households (87,000 people).

- Households whose energy costs are 10% of their income or more - 1,202,567 households (3 million people).

There are several additional indicators, here I will mention just a few of them.

- Residential energy efficiency - 69.6% of all dwellings in Portugal have an efficiency class of C or lower.

- The population with debts for utilities - 4.3% (440,000 people).

Based on the definition of energy poverty, the analysis of selected basic indicators and the comparison with data on social benefits and income. It is estimated that between 1.9 and 3 million people in Portugal are in an energy poverty situation based on their housing conditions and on the criterion of the ratio of income to energy consumption costs.

How the government fights energy poverty

In 2010, as part of the National Energy Strategy, a special preferential electricity tariff was introduced (Law-Decree № 128-А/2010), and in 2011 a feed-in tariff for natural gas was also introduced (Decree-Law № 101/2011). These tariffs are aimed at the most economically vulnerable segments of the population. The feed-in tariff for electricity is available to citizens who receive various social benefits and have a total annual income not exceeding €5,808. However, access to the feed-in tariff for natural gas is more limited, and there are still no benefits for bottled gas. In the context of the pandemic crisis, the social tariff for electricity and natural gas became available to all unemployed people in 2020.

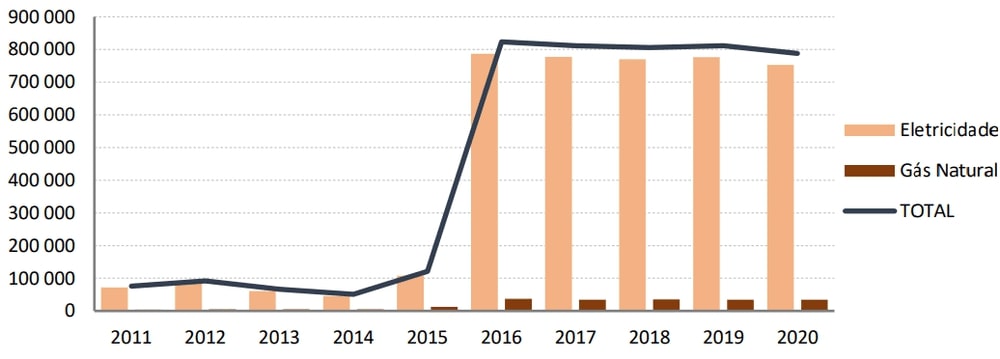

According to 2020 data, the total number of beneficiaries of the feed-in tariff for electricity corresponded to about 14% of the total number of households. The total number of beneficiaries of the social tariff for natural gas was 2% of the total number of natural gas-consuming households. The dynamics of the number of beneficiaries of feed-in tariffs is shown in the graph below.

These measures, while supporting a significant number of citizens in covering their energy costs, do not eliminate the causes of energy poverty.

In 2020, Portugal approved the National Plan for Energy and Climate 2021-2030 (PNEC 2030). This plan aims, among other things, to create a long-term strategy to combat energy poverty, to develop programs that promote energy efficiency and the integration of renewable energy sources.

In March 2021, a set of measures dedicated to energy poverty was also included in the Recovery and Resilience Plan (PRR 2021-2026). For example, 100,000 checks were approved as direct assistance to the neediest families to improve the energy supply to their homes. These and other measures and policies were subsequently developed and expanded in the National long-term energy poverty strategy 2021-2050. This strategy envisages, among other things, the allocation of at least 300 million euros for measures to improve the energy efficiency of residential buildings.

Energy efficiency of residential buildings in Portugal

The first requirements for assessing the heat retention of residential buildings and preventing overheating were introduced in Portugal in 1990. In 2006, the System of Energy Certification of Buildings (SCE) was adopted, a system that allows the energy efficiency of a building to be evaluated on a predefined scale of 8 classes (from A+ - very efficient, to F - very inefficient). It provides owners with current information on the impact of this classification on comfort, health, and energy consumption. Between 2014 and 2020, approximately 1.3 million energy certificates were issued, of which only 12.3% of residences qualified as very efficient (A and A+), and about 70% of certified residences have an efficiency grade of C or lower, as shown in the chart.

Based on the analysis of energy certificates, we can conclude that the national stock of existing buildings does not have the necessary ability to provide adequate living conditions for all its occupants. This includes heat and sound insulation and good indoor air quality.

A large part of the housing stock is obsolete and in need of repair. Whether this repair will improve the energy efficiency of buildings is a big question.

How to evaluate the energy efficiency of a residence

Any home or apartment owner can request an energy certificate for their property. Obtaining this certificate is mandatory for:

- New Buildings;

- Secondary properties subject to major renovations (i.e., those in which the estimated total cost of the work exceeds 25% of the total building cost based on the annually published average construction cost);

- Sale or lease of real estate;

- Buildings covered by funding programs if energy certification is required for this purpose;

- Building owners who are eligible to access tax credits if energy certification is required for this purpose.

To obtain an energy certificate, it is sufficient to apply to one of the many organizations that provide these services, such as SCE. You need to prepare a document package and provide access to the territory. Actually, wait for their decision and get the certificate. It should be noted that energy efficiency certificates have validity periods, which depend on the purpose of the building.

Advantages of having an energy certificate for the property owner

In addition to having a home with a higher energy class has a competitive advantage in the real estate market. Having an energy certificate can help its owner gain access to financing at better rates or take advantage of the benefits of IMI or IMT taxes.

Several tools are available to property owners to support the implementation of improvement measures outlined in the energy certificate. Using the tools listed below, you can access funding or incentives that will allow you to rehabilitate and improve your property.

Program Casa Eficiente 2020 aims to provide loans at preferential conditions for activities that improve the environmental performance of private residences, in the areas of energy efficiency and water conservation, as well as urban waste management. Repairs can be carried out both inside and outside the building.

Owners of residential buildings or sections thereof, as well as their respective condominiums, can apply. Buildings may be located anywhere in the country.

The program IFRRU 2020 is designed to invest in urban renewal and energy efficiency throughout the country. This instrument supports the comprehensive rehabilitation of buildings (multifamily or private houses) that are 30 years old or older (or, in the case of lesser age, that demonstrate a preservation level equal to or less than 2, defined in accordance with the provisions of Decree-Law no. 266-B/2012 of December 31).

Property tax incentives (IMI)

Municipalities, by resolution of the municipal assembly, can establish a reduction of up to 25% of the municipal property tax (IMI) rate in effect in the years to which the tax applies to energy-efficient city buildings:

- When a building is assigned an energy class equal to or greater than A;

- When a building has been given an energy efficiency rating of at least 2 steps above the previous rating as a result of construction or renovation work.

These benefits are valid for 5 years. Check with your municipality to see if and how you can take advantage of these benefits.

Property transfer tax (IMT) benefits

As provided in Article 45 of the EBF, urban buildings or self-contained units built more than 30 years ago or located in urban areas enjoy an exemption from the IMT, provided they meet the following conditions in the aggregate:

- are subject to rehabilitation measures promoted in accordance with the provisions of the Legal Regime for Urban Rehabilitation;

- as a result of the intervention provided in the previous paragraph, the corresponding state of conservation is two levels higher than previously assigned and has at least a good level and the energy efficiency requirements are met.

The IMT exemption arises on the acquisition of property intended to be restored, provided that the acquirer begins the related work within three years of the date of acquisition. Other restrictions also apply.

How not to get trapped in energy poverty in Portugal

As we have seen, a large part of the Portuguese population is, to put it mildly, uncomfortable with the inability to fully heat their homes and use energy services. In order not to follow this sad example, an immigrant should at least strive to choose energy-efficient housing. This can be done by paying attention to energy certificates and striving to earn enough income to pay for utilities without breaking the budget. Unfortunately, WithPortugal.com will not be able to help you with the answer to the question, "How can I make a great income in Portugal?" However, help with finding a place to live can be found here - you can contact professional real estate agents in Lisbon, Porto, Figueira, Algarve, and Madeira who will be happy to help you find a property according to your criteria.

This article was written using fascinating materials published in the public domain. If you are interested in the topic, I suggest you read them:

- University of Lisbon study

- National Strategy to Combat Energy Poverty

- Eurostat

- Website about energy efficiency in buildings

Translated from Ukrainian by Rodion Shkurko